What is Critical Thinking, Exactly?

When I mention that I’m a professor of critical thinking to new people I meet, the most common reaction I get is amazement: everybody thinks that critical thinking is somehow very important.

However, my guess is that not everybody knows what exactly it means to think critically. Most likely, the common belief is no different from the way the U.S. Supreme Court defined obscenity: they know when they see it.

I am not surprised by either the popularity of ‘critical thinking’ as a phrase or the lack of consensus about what it actually means. It is true that there is a lot of confusion about what critical thinking really is.

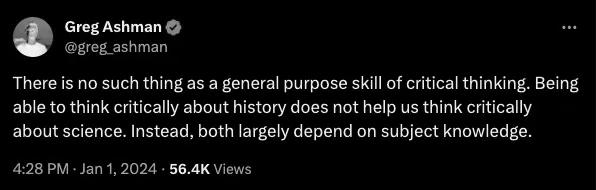

I say confusion, but I could have said denial too because there are some people who don’t believe that critical thinking exists. The claim here is that there is no such a thing as a general, all-purpose skill of critical thinking. For these people, general thinking skills are nothing more than disguised expertise in particular domains, where the knowledge and skills developed by focusing on specific tasks are mistaken for some wider thinking ability.

For example, if one is a good thinker in engineering, or chemistry, that is because they are well-versed in those fields, not because they possess some independent ability. Take them outside those fields, and they may not be that smart. An expert software developer may not be a good thinker when it comes to politics, or art, or something completely unrelated.

I’m sure you’ve met people like that in your life. I surely have. German language has a perfect word for this phenomenon: a “Fachidiot” is an expert in a specific field who is ignorant, narrow-minded, or clueless about other fields or aspects of the real world.

However, I’m also pretty sure you met a lot of people who are not like this. Folks who seem to have a lot of common sense no matter the subject. These may be polymaths or geniuses known from history, like Leonardo DaVinci, Rene Descartes, or Ada Lovelace, or some of our multi-versed contemporaries (or almost-contemporaries) like Richard Feynman, Bruce Dickinson, or Elon Musk.

So, is there a general set of skills we call critical thinking?

Well, there might be, but what exactly are these skills is not crystal clear. Defining critical thinking is notoriously hard because it refers to a diverse set of skills, and not everybody is in full agreement about what skills belong to that set.

Among those believing that critical thinking is a thing, some, like Edward M. Glasser think it refers to:

... the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.

That was a mouthful. The fact that a definition packs so much in a tiny space tells you something about the thing being defined: it’s a weird thing that is not so easily described.

Others offer somewhat simpler definitions. Folks at Monash University in Australia define it as:

… a kind of thinking in which you question, analyze, interpret, evaluate, and make a judgment about what you read, hear, say, or write.

Although different in verbiage, both of these at least revolve around the same set of basic skills. According to them, to be a critical thinker, one needs to be good at:

-

Asking the right questions,

-

Analyzing and interpreting information, and

-

Making value judgments.

As you can see, it’s a very practical set of skills. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it, all of these build around the same core of “careful goal-oriented thinking.”

If we agree with these definitions and accept that there is some fundamental set of reasoning skills we consider the core of what “critical thinking” really is, we’re only half-way out of the woods. The rest of the path will depend on how we go about developing those skills.

What should the lessons that can teach us these skills look like?

How do we go about educating ourselves for critical thinking?

Education for critical thinking

In my decade-long experience of teaching critical thinking, I’ve encountered one frequent misconception about the subject: there are many people who believe critical thinking can be taught (and learned) by simply discussing things in a ‘critical’ fashion (whatever that means). They believe that if we just openly discuss any topic with people we disagree with, we will somehow (miraculously) learn how to think critically.

But, that is not just a misconception. It’s also a grave mistake that can actually hinder a person’s development of the skills we identified as the core of critical thinking: asking questions, analyzing information, and making judgments.

Instead, what is needed is a structured approach that focuses on some concrete and tangible lessons about how to do these three things. Something that is similar to any other academic fields, in the sense that it covers a certain knowledge base, has its own definitions, concepts, theories, and explanations.

The way critical thinking education has taken place so far in universities worldwide is best reflected in the content of available textbooks. Most of them focus on lessons organized around three separate modules:

-

Deductive reasoning,

-

Inductive reasoning, and

-

Thinking fallacies.

Deductive reasoning is a broader term that covers different aspects of formal reasoning under perfect information; that is, under conditions of absolute certainty in the claims we make.

Math and logic are the best examples of deductive reasoning. In both, we accept certain claims to be true and we use these claims to make further ones. Deductive reasoning skills teach you how to generate more knowledge from what you know already by discovering what other claims are implied by, or follow from, the claims you already accept.

Let’s use a simple example so you can see how this works in practice. Suppose you know two things are true: first, that all dogs are cute; and second, that Fluffy is a dog. These two are separate claims. One of them says something about all dogs, and the other says something about some creature called Fluffy: we know that creature is a dog.

Deductive reasoning is when you take these two claims and try to figure out what else is implied by two of them when taken together. It doesn’t take extraordinary intelligence to conclude that these two imply that Fluffy is cute.

Deductive reasoning is like doing mathematical detective work: you skillfully combine claims and look for connections that can help you generate more information. Strictly speaking, deductive reasoning doesn't produce new information; it just helps you reveal what information is hiding beneath what you already see. “Connecting the dots” is a phrase that perfectly describes what we are doing when we reason deductively.

Inductive reasoning is also about connecting the dots, but it is more challenging because it works with imperfect information: claims we can’t be certain about. Any situation in which we have to make conclusions with insufficient information will require inductive reasoning.

For example, we could re-work the earlier example with Fluffy to see how this works. Instead of the first claim (“All dogs are cute”) imagine we know something about dogs with much less certainty, such as “Most dogs are cute.” We can leave the second claim the same (“Fluffy is a dog.”).

Now, unlike the first case, here we can’t be certain that our conclusion (“Fluffy is cute”) will be true. Of course, we can be fairly confident, since our first premise gives us a strong reason to believe it (it says “most dogs” which means it is very likely that it applies to our Fluffy), but this is still light-years away from the mathematical certainty of deductive reasoning. Even though it is likely that Fluffy is cute too, we should not be that surprised if he turned out not to be.

So, inductive reasoning is probabilistic. Here we can only make conclusions whose truth comes in degrees, which gives us more or less confidence that they’re true, but never full certainty.

Finally, thinking fallacies are a set of most common reasoning mistakes people make when trying to think. Since we are fallible creatures and our civilization has been around for some time, philosophers and scientists over the years have collected the most common thinking traps we fall into. These come in two types: formal fallacies, in which the mistake is due to a faulty mechanics of argument construction (for example, trying to derive a conclusion based on just one claim), and informal fallacies, where the mistake occurs when external elements, like emotions, or societal pressures causes us to make a blunder in our thinking.

Most critical thinking textbooks will provide a list of some of these fallacies. There is no fixed number of them, so authors pick and choose their favorite ones. Mostly, you will find fallacies such as ad hominem (when thinkers focus on the person, not the claim), ad populum (when thinkers believe claims because they’re popular), begging the question (when the conclusion is the same as one of the supporting claims, causing circularity) and similar.

While this is all good and important, there is still something that is missing. As I’ve realized through my teaching experience, simply going through the fallacies and learning about them doesn’t move the needle much: you will not immediately start thinking critically just because you know some theoretical concepts and can work out a few examples.

So, what’s missing?

The missing piece

Here’s an unorthodox claim you won’t find in philosophy textbooks, but I'm sure many of my fellow professors will recognize: critical thinking as an academic discipline lacks pizzazz.

Philosophy comes in many flavors, but one of the most popular ones (and the one I work with) is so-called analytic philosophy. This refers to an entire tradition of thinking that prizes clarity combined with careful, step-by-step breakdown of the thinking process. We arrive at truth by looking at claims microscopically and examining what they mean, how they fit within a broader picture, and what they imply. It’s like going through a forest and carefully examining each tree. This is an important process, but one of its unfortunate consequences is that by focusing on individual trees, we often forget to notice the forest: we fail to acknowledge the motivational forces behind thinking as a distinctly human practice.

Critical thinking is not (just) a dry list of recipes about how to derive conclusions from the premises, or a roadmap that helps you avoid potholes in the street. It’s a live practice; it’s juicy and flowing; sticky and gooey, just like that sweet sap beneath the treebark that we like on our pancakes.

But, what I mean by pizzazz here is not just that critical thinking lacks a good story that could be skillfully utilized by marketing professionals to make the subject more popular. I mean something much more profound: what I think is missing is a unified narrative that hits not only at the very core of what critical thinking is about, but also at how it is done, why it is done, and how the many of its elements fit within a bigger picture.

In other words, teaching critical thinking must integrate human existence in the picture. It has to address passion, beauty, anxiety, and all the other elements of the existential dread (or pleasure) we feel every day. Otherwise, as a learner, you will get a very unrealistic picture of what it means to be a critical thinker in the real world, not just in the classroom.

So, the key question here is: how can we learn critical thinking in such an ‘existential’ way? Is there some unifying and motivating concept that could help us do that?

Well, it turns out that there is.That’s the good news.

But, the bad news is that you’re not going to like what that concept means.

You’re basically dying

The concept of entropy was first introduced in the mid-19th Century and since then it has swept through many scientific disciplines, from thermodynamics and statistical mechanics, to information theory and cosmology.

Yet, despite the complexity brought by interdisciplinarity, the core of the concept is relatively simple: in essence, entropy is understood as a measure of disorder.

Even if you’ve never thought about how to measure order and disorder, I’m sure you can easily tell the difference between the two: at any point in time, you can tell whether your room is messy or tidy. Are the books neatly stacked on shelves? Are your clothes neatly folded in the closet? Dishes washed and put away?

When your room is messy, it is in a state of high entropy. When it is tidy, its entropy is low.

I think that entropy is a perfect concept that can help us understand critical thinking in a more profound way. It can connect its dispersed elements into a unified framework, show us how it is tied to our humanity and existence as a whole, and even help with ways we can put it in practice. It is the exact piece we were missing.

First, entropy is not just any measure. According to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, a cornerstone of our understanding of reality, total entropy (in a closed system like ours) tends to increase over time. This means that things naturally tend to disorder.

In essence, things slowly fall apart and become chaotic and disordered. It is an irreversible process, akin to time itself. Leave an apple on the table for ten years, and there won’t be apple there anymore. You’ll find a small heap (if even that) of dust; it will completely disintegrate, turning into nothing.

The most personal example of entropy at work is the simple fact that we’re slowly dying. Our bodies slowly deteriorate and end up scattered as particles in the universe. We begin life as a clump of cells (higher entropy), reach a zenith of order and energy (sometime in our twenties, I guess) and start falling apart as we grow older. Once we die and decompose into dust, we have reached our maximum state of entropy.

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Entropy describes the full circle of life.

This is scary for us. Death is not a desirable state. We avoid thinking about it, even though it hangs in the air all the time. Sometimes we dislike it so much that we work actively to divert our minds from this fact. There are so many actions we do out of simple fear of death, and we’re often completely in the dark about the root motivation.

Here are a few examples:

-

We strive for fame or legacy as a way to achieve a sense of immortality, hoping to be long remembered after we’re gone. Although being famous after death benefits you in no way, many of our actions are driven by this desire. What else could explain why otherwise rich and achieved people late in life decide to run for office or do other publicly visible things?

-

Beyond satisfying some basic (or intermediate) existential needs, money ceases to be that important for most people. It exhibits something economists call diminishing marginal utility: the more money you have, the less it matters to you. If you have only $100 in the bank, another $1,000 means a lot to you; but, if you have $1B, an additional thousand is like a rounding error, an amount you’d consider negligible. Yet, so many people cannot stop caring for that additional thousand; no matter how much they have, it’s never enough. What drives them is not rational: it is fear of death and disorder, and money offers them a sense of control.

-

If men in our culture can’t help themselves but be obsessed with fantasies of immortality through wealth or fame, women obsess about beauty and show irrational fear of aging. No expense is spared to slow down the onset of disorder; to hide the reality that our bodies tend to a higher state of disorder.

To be good thinkers, we must be aware of the forces that shape our actions. Without a unifying narrative explaining why death occurs and how it shapes our everyday experience and affects our thinking, it is hard to avoid these traps.

The concept of entropy helps us do that. It helps us understand that critical thinking is not just an instrumental activity to reach a certain goal, but an existential practice that touches the core of our being.

To think critically means much more than simply being able to process large amounts of information. We already have powerful artificial intelligence machines that can process information much, much faster than humans will ever be able to. So, critical thinking must mean more than that. It is not just about data processing. It is our way to grapple with our most terrible fears.

‘I think, therefore I am’ is not a motto of a goal-oriented thinker or a fast data-processor: it is a cry of a creature faced with the certainty of death.

Thinking as ordering

So, what do we do? How do we translate this motivational charge of the concept of entropy into some actionable steps that can help us think better?

The first step is to understand thinking as a process of ordering the messy everyday experience. Inputs to our senses are nothing more than raw data we have to make sense of. As cognitive scientists and psychologists know, no information comes to our brains pre-packaged. It is the job of our brains to process the data and convert them into useful information.

However, not every ordering system is equally good. We are used to this so much that sometimes we create order when there is none, or create orderings that do not represent reality. This is how superstitions are born. Blowing the dice before rolling them is an example of such an order: it is a belief that when rolling the dice is preceded by some action, the outcome will be favorable to us. Similarly, believing that if a black cat crossed our path, a calamity will fall upon us; or thinking that if a bird pooped on us, this will bring us good luck.

So, the real trick here is knowing what types of order are actually good and useful. That is not easy to do. The concept of entropy is of much help here because it shows us that order is not always (or ever) total, but continuous. Very few things are absolutely ordered or disordered; most of them lie somewhere on a continuous line.

Entropy is closely related to the notions of randomness and probability. It can help us understand the difference between order and disorder even when we’re dealing with unpredictable outcomes.

Here’s an example. Imagine we’re tossing two fair coins ten times. Let this be the outcomes of those two tosses:

Coin 1 = [Heads, Heads, Tails, Tails, Tails, Heads, Tails, Tails, Heads, Tails]

Coin 2 = [Heads, Tails, Heads, Tails, Heads, Tails, Heads, Tails, Heads, Tails]

Look at both sequences carefully. What do you notice? If you had to predict the result of the 11th toss (say, you could make a $1,000 bet on the result), which coin would you rather choose?

To make the point even more obvious, imagine we toss the same two coins a couple of hundred times, and the outcomes of both coins look similar to the ten-toss example (with no particular order in the sequence of tosses in Coin 1 and the alternate ‘Heads, Tails’ pattern in Coin 2).

If the coins were fair, then the probability for either ‘Heads’ or ‘Tails’ on each toss would be ½ and you would not be able to predict the outcome of the next toss with much confidence.

According to probability theory, any sequence of heads or tails would be equally probable to any other (since each toss is independent). However, the fact that the outcome of Coin 2 is patterned would give you enough reason to believe that something is ‘fishy’ with this coin.

The coin would be predictable because of its inherent order and low state of entropy. Critical thinking, although complex and multifaceted, revolves around the process of reducing entropy imposed by our sense experience. It is domain-independent to the degree that it helps us create successful and accurate models of the world (orderings that work).

But, unfortunately, life does not follow easy to see patterns, like the one with our Coin 2. Things are much more complex and recognizing these patterns, more often than not, involves struggle.

Entropy also helps us understand why critical thinking is hard, and why the majority of us never fully develop high(er)-level thinking skills.

As any student who prepares for an exam knows, thinking is tiring and requires a lot of energy (that’s why we get hungry quickly when we’re studying hard). Our brains are the most energy-consuming organs in our bodies. If we take oxygen consumption as a measure of energy, we see that despite being just 2% of our body weight, our brains consume more than 20% of its energy reserves.

Thermodynamics teaches us that the only way to reverse the process of ever-increasing entropy is to expend energy. Reversing the path from disorder to order, in other words, requires effort.

This is a basic fact about our universe. There is no escape from it.

We try to minimize thinking effort by relying on shortcuts. For example, we decide to trust some sources in advance, so we don’t check the veracity of their claims every time (do you double-check things you read on Wikipedia?).

Cognitive psychology calls these shortcuts heuristics, and they are often the source of biases and fallacies that prevent us from thinking critically.

Here’s a few of them:

-

Anchoring Bias: We often rely heavily on the first piece of information we hear (the "anchor") when making decisions. For example, if the first car you see at a dealership is priced at $30,000, you might base your judgment of all subsequent prices around this figure, regardless of the actual value of the cars;

-

Confirmation Bias: We usually favor information that confirms our existing beliefs or hypotheses. For example, if you believe that left-handed people are more creative, you are more likely to notice and remember instances that support this belief and ignore instances that don't;

-

Bandwagon Effect: We all have an embarrassing tendency to do (or believe) things because many other people do (or believe) the same. For example, buying a product because it’s popular, assuming it’s good because everyone else is using it.

Succumbing to biases and fallacies like these happens because we are often too lazy (or tired) to think hard enough. The problem is exacerbated by our lack of understanding of the relationship between critical thinking and energy use. Understanding thinking through the lens of entropy could help. If critical thinking is ordering, and if ordering requires effort, then any true critical thinking must be hard and energy-consuming.

So, the sad truth is this: there are no shortcuts to critical thinking. It is hard by design and we must struggle to believe the truth. It doesn’t come naturally or easily; you will have to sweat.

Context

This article is part of the School of Critical Thinking's unique curriculum.

Some ideas are developed further in books. Others through guided instruction.

If this way of thinking feels unfamiliar, there is a reason for that.